A coal miner turned rare earth behemoth? It’s no exaggeration. Ramaco Resources, with a pocket full of productive and safe coal operations in Appalachia, took a chance on a Wyoming property that may ultimately produce an enormous payday for Ramaco, as a result of an enormous rare earth find beneath the surface. NAM talks to Ramaco’s Chairman, CEO and Founder Randall Atkins about the company and what to expect from the western jewel, as well as its admirable coal-to-product efforts.

By Donna Schmidt

The advancement of critical minerals has given the arena of rare earths a brand-new life, particularly for the U.S. – which currently obtains nearly all of its REEs not from domestic operations, but from Chinese miners. What used to be discarded as a coal byproduct is now being re-examined to gain valuable material, and REEs as a whole have risen to superstar status over the last several years – leading to a healthy crop of news on exploration, development and production plans to further solidify rare earths in the national mining sector.

The journey to the rare earth space was a little different for Ramaco Resources, founded by Kentucky native Randall Atkins, in that Ramaco’s start came about from its eastern metallurgical coal interests. Along the way, a chance (and now a very serendipitous) foray into the western U.S. coal market led to what is perhaps the largest discovery to date of rare earth elements from unconventional sources like coal.

Even Ramaco itself is a relative newcomer; the miner with properties in West Virginia and Virginia was founded in 2011, went public in 2017 and has since grown to a run rate of 5 million tons annually (with plans to expand to 7+ Mtpy as the market allows), over 1,000 employees and reserves of roughly 60 million tons.

Ramaco’s back story

To understand how Ramaco has traveled the road to today means also knowing its history, according to Atkins. It began as a coal reserve acquisition and development company, privately funded and focused on opportunistically seeking out geologically advantaged reserves. Initially its intention was to first create an asset’s strategy and value proposition, then plan and permit it, as it did first with its Elk Creek mine complex in West Virginia, and then ultimately exit.

“It (Elk Creek) was so attractive that we thought the mine was finally ready to go,” Atkins explained. “The traditional exit strategies in a ‘normal’ time would have been to either lease to a third-party coal company to joint venture its development, to sell it, or maybe to mine it ourselves.” The timing was not on the company’s side, he said.

“At that point, in 2015, we looked around – and everybody else in … the space was basically in bankruptcy. So, since we had no dance partners to exit to, we decided to take the leap, further recapitalize the company and then actually start an operating mining company ourselves.”

Atkins, a former JPMorgan financier, brought in a second private equity fund investor the following year, and raised more than $90 million, giving Ramaco the capital and runway to carry forward with its development plans. That slight delay changed everything because a volatile coal market in 2016 saw met prices climb from $80 a ton early in the year to nearly $330 a ton by the end of that same year. With an open road before it, Ramaco decided to launch its IPO early the following year in 2017 before it had mined its first ton of coal.

Growth since then has only been speedy. At press time, Ramaco had nine mine complexes, all of underground mines being room-and-pillar with continuous miner supersections, and three surface and highwall operations. Its workforce total is about 1,000, including its front-line workforce and administration.

The Ramaco portfolio

Ramaco’s portfolio flagships in West Virginia and Virginia are its newest mine, Maben, as well as its mines at Elk Creek, Knox Creek and Berwind.

Ramaco announced in 2022 that it had purchased Maben Coal and the Maben property, located in Wyoming and Raleigh counties in West Virginia, in September 2022 from Appleton Coal. The $30 million deal gave it 31 million tons within the Pocahontas 3 and Pocahontas 4 seams as well as Sewell seam. Tonnage from Maben is trucked to the miner’s Knox Creek preparation plant.

The Knox Creek complex, meanwhile, in Raven, Va., opened in February 2021. Elk Creek in Emmett, W.Va., and Berwind in Berwind, W.Va., opened in 2016 and 2017, respectively. Elk Creek was purchased from Consol in 2012 and Berwind was leased from a private land group in 2015.

“The thesis behind starting Ramaco was to reverse engineer how you could create a coal company if you could start from scratch, and do it in a way which de-risked most of the problems others had with longevity in the space,” Atkins explained of its operational strategy and philosophy. The company had several criteria it wanted to adhere to, which would hopefully allow it both operating flexibility and financial risk mitigation.

“We didn’t like leverage, so we continued to operate with as much equity and little debt as possible. We also didn’t want to have a lot of asset retirement obligations, either, so we didn’t buy other people’s existing mine operations which came with reclamation and other legacy liabilities.” This derisking concept also played into the company’s decision to not try and operate longwall panels at any of the mines.

“From a mining technique [standpoint], aside from the capital aspect, we wanted to essentially have the flexibility of deploying a straightforward lower risk mining technique like using a room pillar/continuous miner. Some of the properties we bought were greenfield reserves acquired from larger existing legacy, coal companies who had thought about long wall usage but had decided not to pursue that on the properties either,” he added.

Atkins pointed out, too, that when assembling Ramaco’s resource base it looked to legacy coal companies with long histories of owning larger reserve portfolios assets that, over time, they did not develop as part of their own mine operations. These offered a fertile way for Ramaco to grow by looking at these very same greenfield opportunities with fresh eyes and from a different development approach.

“Geologically, we ended up with some very strong assets and at very opportunistic prices. This helped us to ‘check the box’ on another criteria that we wanted: which was to try to keep our operations as low-cost as possible,” something it succeeded in by having high coal quality, thick-seamed reserves, buying right and then opting to extract via less expensive room and pillar operations.

Headwaters of Brook

With a handful of successful met coal operations in Appalachia, what made a potential coal buy in Wyoming of all places, so attractive?

“When we got started we were looking at a number of different properties in a number of places … we were the new kids on the block looking to quickly acquire assets,” Atkins said of 2011 talks with Brinks, the armored car company, which was looking to divest interests in Pittston Coal, which had used to be its coal and energy business arm. It ended up being an offer he could not refuse.

“They said, ‘Well, we got one deal left. It’s actually out in Wyoming. We’ve owned it since 1912, we haven’t mined or done anything with it since 1970. If you want it, we’ll sell it to you for two million bucks – but you’ve got to close in a month with no questions asked,’ and we said, ‘Okay, why not.’”

After reviewing the reserve reports, Ramaco said its original intention was to invest in the planning and permitting the property, then sell it – much like its initial business model. What it did not know at the time was that the Brook mine, located outside of Sheridan, would turn out to be what Atkins called a “rare earth proposition” that has turned into so much more. In addition to its potential value as both a coal mine and future REE critical mineral behemoth, it also set the tone for Ramaco’s turn toward exploring the technological use of coal to make advanced carbon products and materials, achieved by using coal as a precursor feedstock.

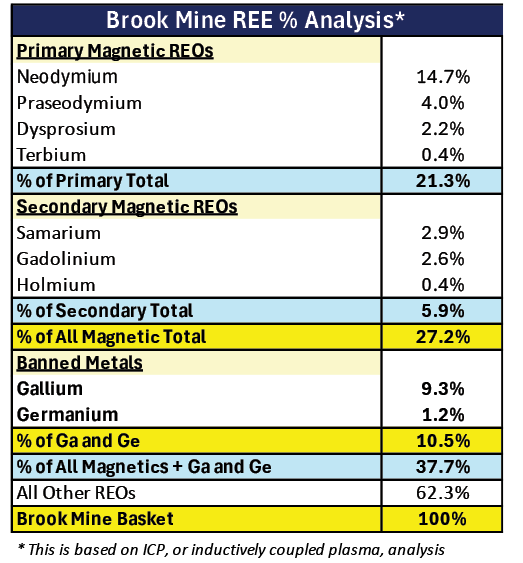

In May 2023, Ramaco revealed that in tandem with the Department of Energy’s National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL) it had made a “major discovery” of magnetic rare earth element deposits at Brook following an 18-month core drilling and chemical analysis program. The work, done with NETL and geologists at Weir International, showed core samples that confirmed “highly promising and world-class MREE and HREE accumulations” and suddenly ranked the asset as one of the world’s highest potential unconventional REE deposits – including Chinese HREE deposits.

“The majority of REE deposits outside of China are associated with ‘conventional’ mines and found in igneous hard mineral deposits, which are both physically hard and radioactive. This makes them both difficult and expensive to mine and problematic to ecologically process and refine,” Ramaco said at the time. It noted that – in contrast – the REEs from Brook are characterized as “unconventional” because they were largely found in softer clay strata above and below the coal seams themselves and were not radioactive.

The retained consultants said the deposit could be mined with normal surface mining techniques and perhaps also via novel deeper in-situ injection well forms of mining. It could also be separated and processed in a more economic and environmental manner than conventional REE mines.

“We and NETL believe the mine contains perhaps the largest ‘unconventional’ deposit of REEs discovered in the United States,” the company confirmed upon learning the news.

Initial mine development at Brook, a site exceeding 15,800 acres, began in late 2023. It stands as one of the largest privately controlled mineral reserves in the western United States.

In March 2024, the miner said new findings from Weir indicated overall tonnage estimates now stand above 1.5 million total in-place rare earth oxide tons, and concentrations average stands at almost 550 parts per million (ppm). Importantly, a number of material lithologies showed maximum ppm concentrations exceeding 9,000 ppm. What’s more: over 10% of the Brook mine deposit was estimated to contain gallium and germanium, which are two high value critical minerals, the export of which was recently banned by China. These figures continue to be revised as new testing results are received and analyzed.

What was going to be an asset that Ramaco had at one point considered letting sit idle, or maybe even abandon, spurred it to “switch gears,” and as Atkins said, keep moving it forward as a very low-cost development operation while simultaneously exploring to look at alternative uses for coal. “It’s one of those things that we picked up, almost as a fluke. In hindsight, its turned into something a heck of a lot bigger than anybody probably anticipated,” he added. “Sometimes it’s better to be lucky than smart.”

REEs and coal-to-products

Before some of its coal contemporaries began making their respective ways into the coal-to-product sector, Atkins said it began working with the Department of Energy on a research grant project alongside the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Terra Power and others called “Coal to Cars.” The focus of the initiative was disover how to use coal to make low-cost precursors for carbon fiber – an idea that hadn’t had much attention as a new technology. The concept was to use carbon fiber that could lighten the weight of vehicles by up to four times compared to steel compontents and also cost less than petroleum-derived traditional carbon fiber.

From that seed came a still-growing tree of coal-based alternative carbon use research. This led Atkins and Ramaco to explore using coal as a feedstock to make synthetic graphite, graphene, activated carbon for direct air capture and even building products and materials. The company also annually hosts a research symposium in Wyoming in partnership with the International Energy Agency’s carbon affiliate on the topic of alternative uses of coal. It has now developed new technologies with more than 20 issued and active patents along with over 70 patented forms of processes. This research and development work is independent of the on-going work it is doing in the rare earth space and is done under the mantle of Ramaco Carbon, also an arm of Ramaco Resources. It, too, began as a private holding but has since been merged back into the public financial umbrella.

Atkins said it continues to work heavily with the company’s first partners, the DOE’s NETL and the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, along with research teams from universities across the U.S. such as MIT, Rice, the University of Kentucky, West Virginia University and the University of Utah as well as strategic corporate partners. Ramaco Carbon also has developed a research campus, the iCAM (innovation of carbon advanced materials), adjoining its Brook mine site north of Sheridan, Wyo.

Much like many know of the Silicon Valley, Atkins said his future view for coal is the growth of a 21st century idea: The Carbon Valley, where carbon from coal makes high value advanced products and materials. Our mantra has been “Coal is too valuable to burn,” he stressed. “Indeed, we refer to coal as ‘Carbon Ore’ since that is how we envision its use.”

Ramaco is making its way there, that’s for certain. As it advances its research campus and coal-to-products endeavors, it is also making strides with the Brook mine in Wyoming. It is looking forward to a technical economic analysis on the property by the end of this year from from Fluor Corporation and has already commenced conversations with customers on future offtake agreements.

“Once we’re hopefully in commercial production on critical minerals, we’ll be operating on all cylinders on both sides of the country at the same time,” Atkins noted. He and his company are both ready, especially when he now knows that the rare earth element deposit seams run deep and likely throughout the entire property. Brook’s value, in fact, has been estimated by others in the tens of billions.

“The U.S. uses about 10 tons of REEs a year, so at least on paper, with 1.5 million tons and counting, we have 150 years of supply for the entire nation,” Atkins said. “When we are in production, this will be the first new rare earth mine since 1952 – and the only mine in the world that is a coal mine producing rare earths. Who said coal couldn’t be cool.”

The Ramaco Foundation

Ramaco is proud to be both a member and supporter of its neighboring communities in West Virginia, Virginia, and Wyoming. Through the Ramaco Foundation, it supports local charities that are results-driven and have proven records of success, partnering with them and expanding their valuable work. These include charities that fight childhood hunger, local rescue and firefighters, and career development. The Ramaco Foundation is dedicated to building meaningful philanthropic relationships in the regions where the company operates and strengthening the local social and economic fabric.