See the four ways process industries can break out of the talent trap.

By Karthik Valluru, Christine Wurzbacher, Gözde Yalazı Özbek, Duncan Melville, Simon Pitt, Chirag Thaker, and Vinciane Beauchene of Boston Consulting Group

After years of conserving capital, companies that operate in process industries – metals and mining, chemicals, building materials, forestry, paper and packaging, and agriculture – are reinvesting in growth. However, the challenges they face in the talent market are making their strategies more difficult to execute.

On one hand, process industries are coping with a tidal wave of retiring seasoned talent, and the consequent loss of decades of institutional knowledge. Conversely, they must significantly expand workforces by 2030 to sustain growth. But these companies are unable to attract talent, especially in the numbers they need, because younger workers usually prefer career paths in urban centers rather than in the rural operations of many process industries. As the demand for talent rises and the supply declines, process companies are being pushed into a talent trap.

Breaking away

Breaking out won’t be easy, but our research shows that business leaders can do so by rethinking how they attract, organize, motivate and lead people as they strategically deploy digital technologies such as generative AI (GenAI). A good starting point is adopting zero-based design, which can help leaders redesign organizations for more productivity.

Getting serious about strategic workforce planning is critical to developing talent pipelines and drawing up global talent sourcing strategies. At the same time, the corporate center’s role must be recast with the aid of activity-based analysis to ensure clarity of purpose, priority and accountability. It’s also critical for process companies to infuse joy in employees’ work lives. The best way of doing that is to groom generative leaders, who can help increase employees’ happiness levels at work and provide them the autonomy and flexibility they need to deliver results.

These approaches and tools, which top management teams can use to navigate the talent market, are the focus here.

The talent market’s dynamics

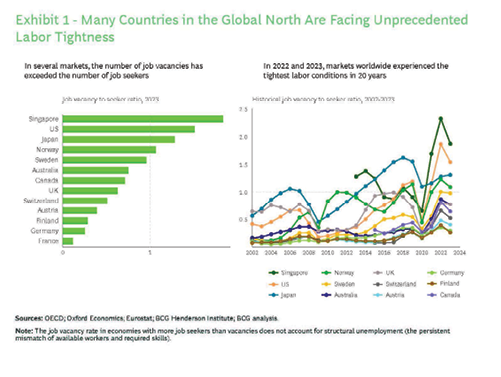

Although it’s often overlooked, business has contended with an ever-tightening talent market since the turn of the 21st century, with the number of job openings continually exceeding the number of job seekers. (See Exhibit 1.) Many of the countries in the Global North have been plagued by this problem; the U.S. had 1.5 times more job openings than job seekers in 2023, for instance, while even in Japan, the ratio was 1.3. In fact, in both 2022 and 2023, most countries experienced the tightest conditions in the labor market in more than 20 years.

Even in the handful of countries in the Global North that had more job seekers than job openings in 2023 – such as Austria, Canada and Germany – the mismatch between the skills needed and those available was evident.

One telling statistic: In 2023, as many as 77% of employers reported difficulties in hiring candidates with the right skill sets – more than twice as many as the share in 2013, according to the International Labour Organization’s report “World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2024.” Contrary to popular perception, the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 isn’t the root cause of business’s travails in the talent market. The U.S., for instance, has seen talent shortages since 2017, as have other Global North countries, including Australia, Japan, Norway, Singapore and Sweden.

Several tectonic shifts have converged to exacerbate the talent crunch. In the Global North, aging workforces have been a major contributory factor.

As the proportion of older people in populations has risen, one result has been an exodus from the labor market. For instance, when the U.S. stock market revived in 2021, more than 47 million people in the U.S. voluntarily quit their jobs.

In emerging markets, including Brazil and India, about 65% of the population have come of working age in 2022. India, Indonesia and Vietnam couple the potential for innovation with relatively low labor costs. But companies still face challenges in emerging markets. That’s mainly because of low labor-force-participation rates and the lack of skilled talent. In India, for example, the labor force participation rate is roughly 55%, dropping to just 37% in the case of women, compared with the OECD’s average rate of 75%.

A global, and generational, examination

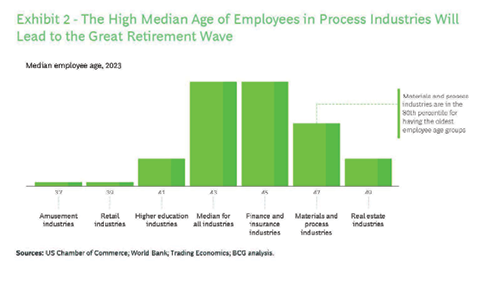

A tight talent market hurts process industries. Companies in process industries are feeling the talent economy’s constraints keenly for two reasons. One, the great retirement, or the exiting of Baby Boomers from the workforce, is leading to acute shortages of talent in those industries. (See Exhibit 2.) For instance, 40% of work site leaders in France’s construction industry will retire in the next 15 years, as will the same percentage of U.S. farm operators.

Workers’ retirement not only will result in the loss of organizational knowledge but also will require training fresh talent, which takes a lot more time and effort in process industries than it does in other sectors.

Two, process companies face a greater risk of attrition because of work fatigue. According to our surveys, in 2023, 53% of frontline workers admitted that they were burned-out and 43% were looking for a new job. These factors are bound to affect productivity and hurt bottom lines, with less-experienced employees unable to deliver the same results as their predecessors. Companies may postpone the problem by signing consulting agreements with recently retired employees, but it isn’t a long-term solution.

Labor shortages will only worsen. Tougher times may be in store, with the prevailing labor shortages compounded by industries’ need for new skills and capabilities. First, the proliferation of digital technologies has resulted in demand exceeding the supply of high-tech employees, such as software engineers and data scientists. Every industry wants software talent, but few prospective employees want to work for nondigital companies.

Second, the shifting centers of production worldwide are forcing companies to look for talent in new regions. Nearshoring has led to demand for manufacturing talent in Global North countries such as the U.S., where talent is in short supply. Agriculture is expanding further north in Canada and Russia as global warming renders colder areas more suitable for crop cultivation. And mining companies are exploring new regions where skilled talent is scarce.

Third, the rising political and societal expectations worldwide around sustainability are forcing process companies to look for talent from other sectors and to retrain existing employees. For instance, instead of only gauging financial optimization, mine planners are increasingly expected to estimate the impact of expansion plans on parameters such as wildlife habitats and recreational land use – a task that many were not trained for even a few years ago.

Above all, the younger generations have more negative perceptions about process industries, making it more challenging for these companies to attract talent. In the UK, only 2% of people who are 18 to 24 years old say they want to work in manufacturing, while in Canada, the number of mining graduates has dropped by 50% since 2015.

Process companies have tried to show that they aren’t the same as their smokestack predecessors. (Remember GE’s 2015 ad campaign, What’s the Matter with Owen?) But they haven’t recaptured their luster – yet.

Rethinking talent strategies

Despite the many challenges they face, CEOs in process industries can navigate the troubled waters of the talent market by acting on four fronts.

Deploy strategic workforce planning – really. Chief human resources officers in process companies have to start proactively building talent pipelines rather than thinking they can pick and choose people whenever they need them from existing pools, which are drying up. That’s why HR leaders need to be involved in business planning and be given a seat at the table when process companies make investment decisions.

Organizations would do well to adopt strategic workforce planning (SWP) to ensure they have the right people with the right skills in the right positions at the right times. In our experience, many process companies don’t use SWP, and even those that do aren’t always getting it right.

SWP entails forecasting future workforce needs on the basis of organizational objectives as well as undercurrents, such as technological advancements, industry shifts, and demographic trends.

By using SWP, companies can identify the gaps between the current workforce and future needs, spot labor market trends, and make optimal decisions about talent acquisition, development and deployment – early.

Apart from data, periodic workshops informed by market trends, competitor analysis, and customer surveys will help identify the likely changes to talent requirements. In fact, understanding skill gaps from a future role-requirement perspective also helps identify how best to fill them. Assessing staffing opportunities merely by evaluating skill sets and job descriptions is too narrow an approach in the current marketplace.

SWP exercises can also help assess global sourcing strategies. For instance, process companies could enter or expand in talent-rich markets, such as Brazil and India, to tackle shortages, since these workforces are just reaching working age. Setting up remote operating centers, as BHP and Linde have done in Australia and the Asia-Pacific region, is another way of tapping talent in markets where it’s available.

By way of illustration, applying SWP at a U.S.-based agricultural equipment manufacturer recently revealed several gaps in its workforce needs over the next five years. It found that its requirements for roles such as data scientists, data processors, and systems engineers were as high as three times the then-projected levels. By anticipating needs more accurately and augmenting its talent spotting and evaluation processes, the company was able to reduce hiring times by 20 to 30 days – a 20-35% improvement – which helped it meet its talent needs as they arose.

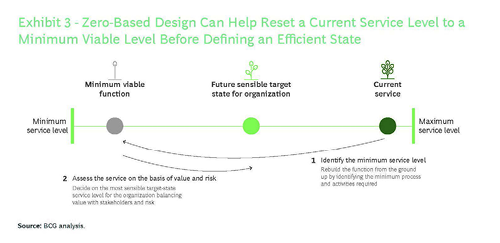

Embrace automation to improve productivity. Industrial manufacturers must continuously increase the productivity of their existing employees by redeploying them to more productive areas. They can ensure that by using a combination of zero-based design (ZBD) and digital technologies, such as GenAI and automation.

ZBD can help organizations reengineer organization structures that have become too complex and drag down productivity. (See Exhibit 3.) By using this approach, which involves evaluating and justifying every role and activity from the ground up, companies can judge the necessity of functions and processes. Companies can also use ZBD to simplify complex processes and free up employees to take on higher value tasks.

But ZBD shouldn’t be used as a one-time effort. Rather, it should be used continuously to trigger a mindset change that gets embedded in the organization through new processes, roles, and responsibilities. For instance, in 2021, a Canadian mining company used ZBD to evaluate its functions and processes in the face of declining demand. After identifying the activities that were most critical for customers and benchmarking itself against peers, the company retained only the minimum number of activities necessary to conduct its operations safely and effectively. The exercise has led to productivity increases of 30-45% in some areas.

In addition to adopting ZBD, process companies must revisit the business case for investing in digital technologies. Digital technology costs have fallen sharply over the past decade even as skill sets have improved rapidly; with GenAI’s advent, they are likely to fall further.

Deploying digital technologies is just the first step, though; most of companies’ gains come from coupling them with process changes, workforce retraining, and new operating models. For example, three years ago, a global pulp-and-paper producer deployed a planning optimization tool with 300,000 decision variables, 90,000 constraints, and 25-plus data sources. By using the digital tool as well as redesigning processes and retraining employees, the manufacturer was able to cut the time it took to develop production plans from seven days to two hours. Responding faster to market shifts led to a 5% savings in the company’s costs of harvesting and transporting raw materials.

Reimagine the corporate center’s role. Process companies, many of which are large and globally dispersed, must revisit the center’s role and decision rights in today’s connected world. Because of remote operating centers, new capability needs, and strategy shifts, centralizing or decentralizing decision making isn’t as straightforward as it used to be. That’s why it’s important to adopt an activity-based approach to decision-making rights.

The starting point must be to define the organization’s guiding principles, such as its vision and strategy, without which structures and decision rights can’t be aligned to business needs. For example, companies with focused business portfolios, or similar manufacturing facilities, are likely to benefit from a centralized approach to generate economies of scale and standardized processes. By contrast, multi-business organizations that are focused on top-line growth may find it better to let strategic business units take the lead in generating sales, which will grow revenues faster. These units can also build the muscle to weather potential geopolitical fragmentation by encouraging local decision making and multilocal operations, while maintaining global standards in critical activities.

Activity-based analyses can also be used to design centers and central functions that suit companies’ needs. Performing an activity analysis, while being guided by an overarching organization design philosophy, will ensure a balance between granularity and pragmatism, as well as prevent highly fragmented and confusing organization structures.

The centralized technology function of a global metals and mining company unexpectedly found itself having to take on a large number of low-value projects. Those tasks were far removed from the function’s usual operations, increasing its cycle times, headcounts, and costs. So, the function recast its role, aligning its subfunctions with the company’s regional business units and strengthening its contractor management capabilities to improve accountability and reduce handovers. By reprioritizing its projects portfolio over a two-year period, the technology function reduced headcount by 55%, cut its budget by 30%, and shrank delivery times by half.

Grow generative leaders. Industrial companies, whose image as employers of choice has faded, must transform employee value propositions if they wish to attract and retain talent.

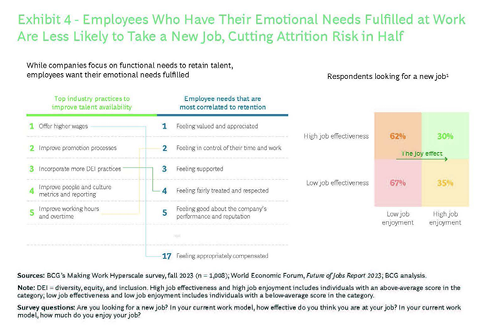

Meeting employees’ functional needs, through compensation and benefit packages, is just table stakes. In a competitive talent market, that’s far from sufficient. Wise employers increasingly prioritize the sense of fulfillment in their work environments.

Several BCG surveys confirm that employees seek emotional fulfillment at work, affecting retention. (See Exhibit 4.) One BCG survey showed that employees who enjoy their work are 49% less likely to say they would consider taking a new job than employees who don’t enjoy their work – an outcome that we call the joy effect. This finding echoes another BCG survey of more than 11,000 workers that identified “doing work I enjoy” as the factor with the third strongest correlation with one-year retention, behind only job security and feeling respected.

Leaders are the most critical driver of employees’ experiences. In fact, satisfaction with managers is correlated with joy at work.

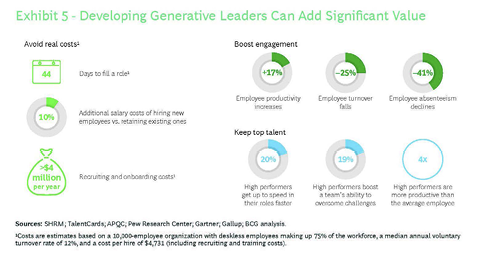

Generative leaders – who reimagine and reinvent the business to serve all stakeholders, inspire and enrich the human experience, and execute and innovate through charged teams – are more empathetic to employee requirements. This type of leadership results in an increase in worker engagement by 5 to 7 percentage points that, in turn, sets off a virtuous cycle of additional benefits. (See Exhibit 5.) The gains include up to a 17% increase in productivity, a 25% reduction in turnover, and a 41% fall in absenteeism.

Two years ago, a global food manufacturer was struggling to fill approximately 3,000 open positions. Training its vice presidents to become generative leaders resulted in several short run and long-term advantages. Almost immediately, employee complaints and enquiries fell by 90% and employee satisfaction levels improved by 20 percentage points. Over time, the company recorded a reduction of 42 percentage points in overtime hours, an annual savings of $85 million, and a decrease of 46 percentage points in employee turnover.

As the talent market becomes tougher, process companies will have to learn to use all these approaches and tools to thrive.

To be sure, each company’s starting point will be different, and it will determine the right set of measures that it must take. Even so, improving productivity, better forecasting talent needs, delegating control optimally, and creating a joyous workforce will enable process companies to turn the talent challenges they face today into a distinct people advantage tomorrow.

Boston Consulting Group is a global consulting firm that partners with leaders in business and society to tackle their most important challenges and capture their greatest opportunities. Our success depends on a spirit of deep collaboration and a global community of diverse individuals determined to make the world and each other better every day.