Burgex Mining Consultants offers a deeper look into what’s driving movements and changes across several commodities in this outlook.

By Chris Guenther

When considering commodity markets, I often liken them to a game of blackjack. With the wealth of data now at our fingertips, it feels akin to openly counting cards in the resource sector, and surprisingly, no one seems to mind. This is a boon for those who value this sector, not only for personal gain but also for the broader success of humanity. A deeper look reveals that investing in the resource sector is, in many ways, a wager on the continued success of our species. If we can successfully navigate and overcome the current challenges, there’s a promising horizon beyond this difficult phase.

Throughout history, there have been those who predict doom for humanity, forecasting various forms of collapse. This sentiment is not new, as the adage goes: “Bears make headlines, bulls make money.” Our psychological wiring favors attention to negative information, a survival mechanism ingrained in us.

Yet, we’re at a point where the primary obstacle to our prosperity is self-imposed limitations. We’ve shifted from a focus on sheer survival to addressing how we can efficiently and sustainably manage resources to meet the needs of the global population. This shift from survival to efficiency presents new challenges, and our collective psychology is still catching up.

At the heart of many of our challenges are issues of war, conflict and power dynamics, often perceived through a lens of oppressor versus oppressed, particularly by younger generations. This perspective is influenced by the history of colonialism, where resources were exploited to build economies at the expense of local labor, economies, and environments. How do we move forward from this historical context and disentangle the resource industry from its problematic past?

The growing awareness of climate change and environmental concerns has led some to view all extractive industries negatively. The extreme view suggests reducing the population to alleviate resource demand. However, this overlooks humanity’s adaptability and problem-solving abilities. We have a history of technological and social advancements at crucial junctures. Optimists believe we will continue to do so, overcoming obstacles by transcending social, political, and global barriers for our collective benefit.

This article aims to identify a few key challenges facing the resource sector and the opportunities that may ultimately happen for those who can overcome them. Key questions arise: Are we experiencing a fundamental shift in markets, where investment flows from tech stocks and equities to tangible assets like commodities and energy? With the end of the decades-long trend of falling interest rates, and the onset of persistent inflation, what implications does this have for those in the resource sector, and for investors? How long will it take for the general public to recognize this shift, conditioned as they are by the long-standing bull markets in stocks and bonds? And crucially, what will be the impact on the resource sector when this awareness becomes widespread?

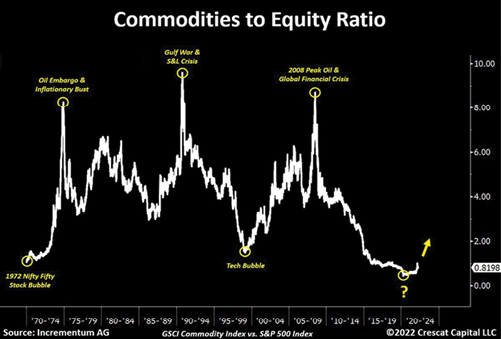

The following chart provided by Tavi Costa from Crescat Capital illustrates the cyclical nature of commodities in comparison to general equities, and it pinpoints our current position in this ongoing cycle.

Historical peaks on this chart mark instances when commodities have soared in relative value to the S&P 500 – indicating periods when they were considered expensive or overpriced. Conversely, the troughs represent moments when commodities were at their most undervalued in relation to equities. Our present position in this cycle strongly suggests that, unless we have mastered the ability to produce physical resources such as copper and lithium with the same ease as creating digital tokens, we may very well be in the initial stages of a commodities bull market, especially in terms of relative value to general equity indices.

At present, several factors are limiting resource production, leading to an increasingly supply-constrained environment. This tightening scenario has far-reaching implications for stakeholders in our sector, from the largest conglomerates to the smallest enterprises, and it is likely to influence the direction of capital flows into the sector for the foreseeable future, potentially spanning years or even decades.

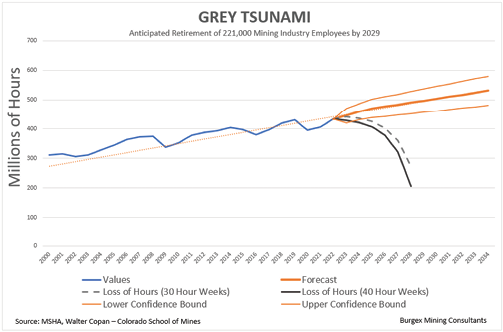

A forthcoming challenge is the demographic shift within the mining and resource workforce, which indicates a significant retirement wave of skilled and experienced labor in our industry.

The Grey Tsunami

The mining industry often finds itself misrepresented in the press and on social media as an antiquated, environmentally detrimental sector. This portrayal is paradoxical considering our growing need for metals to achieve decarbonization and enhance energy efficiency. Furthermore, mining has been overshadowed by the allure of technology and finance sectors, which have captivated the labor interest and capital of the past four decades due to their perceived ease and lower risk, compared to the tangible and technical demands of resource extraction.

Walter Copan, VP of Research and Technology Transfer at the Colorado School of Mines, highlights a staggering trend: “We are on the cusp of a significant workforce depletion with over half of the U.S. mining workforce set to retire in the next six years – amounting to 221,000 skilled workers by 2029.”

This ‘Grey Tsunami’ threatens to erode not just the workforce numbers but also the accumulated wisdom and expertise that only decades of specialization can imbue, at a time when mining’s importance is reaching an unparalleled zenith.

During a testimony before the House Committee on Natural Resources in June, Copan underscored the scale of our copper demand: the next quarter-century will necessitate more copper than has been produced throughout all human history. This figure translates to 700 million metric tons – enough to fill a cube measuring 430 meters on each side. The comprehensive recyclability of copper is offset by its extensive use in long-life infrastructure, rendering it inaccessible for reuse.

As we pivot toward decarbonization, the demand for copper will only intensify, particularly for upgrades to the electrical grid to support a more electrified globe. Moreover, the push for modern amenities in developing regions – refrigeration, air conditioning, and beyond – is just beginning. While the Western world enjoys the fruits of industrialization, a substantial portion of humanity is on the cusp of laying down the foundations of their own industrial and technological revolution, heralding an unprecedented demand for more commodities.

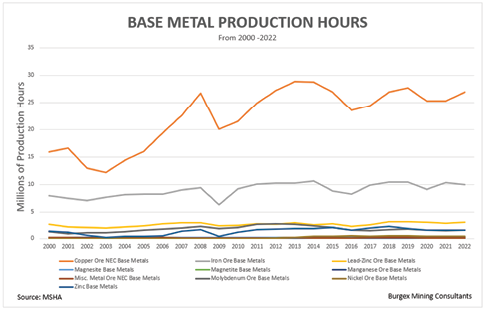

Continuing our focus on copper, the above chart tracking base metal labor hours in the United States, as monitored by MSHA and compiled by Mineralocity, reveals a significant trend: the man-hours required to produce copper have climbed from approximately 15 million in the year 2000 to 27 million today. Our industry’s need for labor is more pressing than ever.

Compounding the issue of the ‘Grey Tsunami’ – the wave of experienced workers nearing retirement – is the reality that large, high-grade, and easily accessible copper deposits are becoming increasingly scarce. We’re not facing a shortage of copper per se, but what remains is more challenging to extract: it’s situated deeper underground, of lower grade, and often in regions that are geopolitically complex or constrained by stringent regulations shaped by social and environmental concerns.

The copper is there, but the hurdles to its extraction have multiplied, encompassing technical difficulties, protracted production timelines, and heightened costs. In the United States, for instance, the permitting process for a new mine can span over eight years.

As a result, the production of each pound of copper demands more labor than it did two decades ago. Meanwhile, the pool of workers capable of meeting these strenuous demands is diminishing precisely when they are needed most. This confluence of factors is creating a ‘perfect storm’ for a supply-constrained commodity market, with potential ramifications that could reverberate across the global economy.

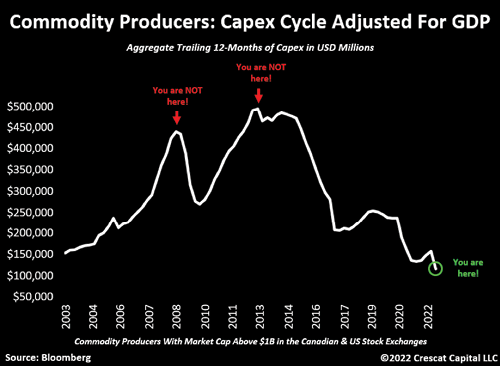

This labor force dilemma is further compounded by the capital expenditure (capex) cycle in the commodity sector, as delineated in the accompanying chart from Tavi Costa:

Globally, our investment in capex – adjusted for GDP – for sustaining current production and developing new deposits has plummeted to its lowest point in two decades. We saw capex reach its zenith in 2008 and again between 2012 and 2014, followed by a stark downward trajectory.

Despite the reduction in capex, production levels have remained relatively stable, and commodity prices have been subdued, for the time being. However, this begs the question: What effect has the reduction in capex had on the discovery of significant new deposits?

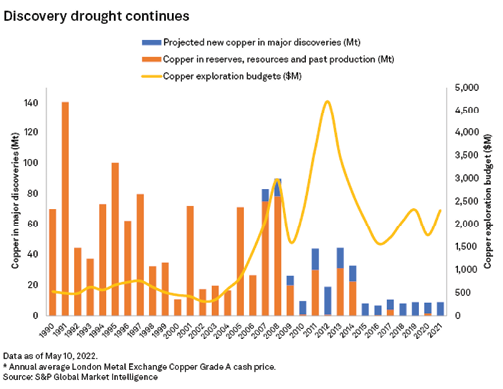

The boost in exploration budgets observed from 2007 to 2013, despite being substantial, failed to make an impact comparable to that of the 1990s. Presently, while exploration budgets are still higher than what we saw from 1990 to 2006, the actual and projected growth in mineable copper inventories is at a three-decade low. This indicates a continuation of the supply-side constraints, adding yet another layer to an already complex scenario.

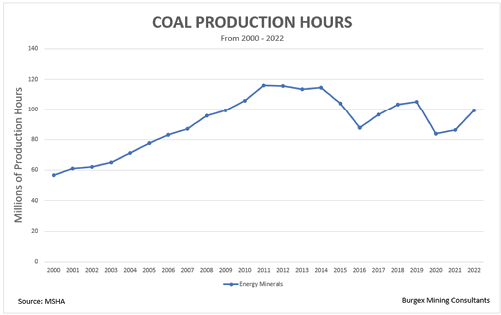

Examining coal production hours, which have stabilized around 100 million annually since 2007, it becomes clear that the energy sector may confront more than just escalating prices – coal remains a cornerstone for electricity generation both in the U.S. and internationally. Beyond the immediate implications for pricing, there looms the threat of potential scarcity, a problem that could precipitate far-reaching consequences beyond mere price surges. A pressing question arises: what will the landscape of coal mining look like when the seasoned workforce, standing at the precipice of retirement, opts for well-deserved respite? This scenario casts a shadow not only on production volumes but also on the industry’s ability to sustain its operational expertise.

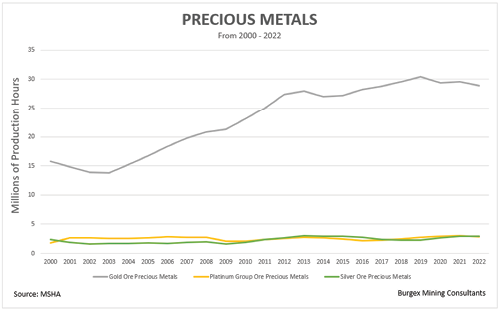

Lastly, examining the production hours for precious metals unveils a compelling scenario, especially in gold production. Silver, often extracted as a by-product of base metals such as copper and zinc, shares the production fortunes of these metals. With silver’s escalating role in electronics and solar technologies the prospect of supply constraints significantly impacting manufacturing processes is not just hypothetical but imminent.

Gold, while sharing applications in electronics and industry, is carving out a pivotal role amidst shifting global macroeconomic conditions and de-globalization trends. Nations are gravitating towards a neutral reserve asset that transcends individual geopolitical influence and is immune to default – qualities inherent to gold. Should this trend persist, gold may emerge as a bastion of stability for both national reserves and the diversified portfolios of retail investors and fund managers alike.

Mining financier Rick Rule frequently cites a striking statistic: the long-term average allocation to gold in investment portfolios is 2%, yet it currently hovers around 0.5%. Even a modest shift in portfolio strategies towards gold for risk mitigation could exert a significant demand pressure, further complicating the supply-side challenges explored here. Such dynamics presage a particularly intriguing period for the resource sector.

In the intricate game of blackjack that is the resource sector, an adept player – armed with a wealth of data akin to counting cards – stands to reap significant benefits. Yet, surprisingly, the vast potential of this sector remains largely underappreciated, despite its crucial role in the advancement of humanity.

As this article has highlighted, the resource sector is navigating through a series of compelling challenges. The ‘Grey Tsunami’ of retiring skilled workers, the precipitous decline in capital expenditures for sustaining and developing new deposits, and the resulting scarcity of significant new discoveries are combining to create a supply-constrained market environment. The copper industry, specifically, faces the daunting task of producing more with less, as easily accessible deposits dwindle and remaining reserves are harder and costlier to extract.

Coal, still a linchpin in global electricity generation, also stands on the brink of a potential shortage, not just in terms of resources but in the invaluable expertise of its aging workforce. Similarly, the precious metals sector, with gold and silver at its helm, is at a crossroads where demand for technological applications and macroeconomic stability could drive unprecedented market dynamics.

The mining and exploration industry is a game of strategy and foresight, much like a well-played hand of blackjack. Within this arena, companies like Burgex Mining Consultants stand out for their dedication to playing this complex game with both passion and precision. The suite of services, from land research to economic modeling and project management, plays a crucial role in enhancing efficiency, ensuring sustainable practices and driving the sector forward.

Just as in blackjack, where success hinges on understanding the deck and playing the odds, the resource sector demands a deep knowledge of its dynamics and a commitment to long-term strategies. We are not just participants in this game but are shaping its outcome. By leveraging human ingenuity and a spirit of innovation, they’re not only navigating current challenges but also setting the stage for future triumphs. Together, they stand ready to make the most of each hand dealt, turning calculated risks into sustainable rewards, and continuing to bet on the resource sector as a pivotal player in the advancement of civilization.

About the author: Chris Guenther is finance director for Burgex Mining Consultants.

A new relationship with the material world

By Walter G. Copan

In the race for critical minerals, the rarest element may be a skilled mining workforce. A new bill in Congress is a good start.

As the world rapidly accelerates its transition to a clean energy future, the United States is waking up to the reality that achieving global clean energy goals will require more materials: more mining, recycling and, perhaps most importantly, the skilled workforce to deliver them. To be blunt, the mine of the future cannot look like the mine of the 19th century.

Electric cars, solar panels, electric power generation and low carbon energy technologies all require critical minerals that are mined from the earth. We now need many of these materials in unprecedented quantities and at pressing speeds to deliver for clean energy, semiconductors, and other industries. To achieve global clean energy goals, the world may need as much copper over the next 30 years as has been produced since the dawn of civilization.

Over the past decades the U.S. has de-emphasized the need for domestic mineral resource development and starved investment in mining innovation. It has instead relied upon international sources, many of which are based in adversarial countries with low environmental, labor, and human rights standards. Of the 50 minerals and metals on the list of critical materials published by the U.S. Geological Survey, 30 are primarily produced in one country – China.

Many in industry, academia and government see a pressing need to innovate and rapidly produce reliable, environmentally sustainable, socially responsible, and economically sufficient supplies of minerals to realize our shared clean energy future. However, these solutions may be undermined by an even more concerning shortage: a skilled workforce of mining and mineral processing engineers ready and willing to drive and implement the needed innovations.

Recently, Congress recognized its own role in investing in the mining workforce. This year, the House Committee on Natural Resources held a hearing on the bipartisan Mining Schools Act, and the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources voted its bill out of committee, a meaningful step toward helping institutions attract new students to accredited mining and related academic programs. Such bipartisan legislation can help the U.S. to inspire students to meet critical mineral demands while advancing our values and standards.

That support cannot come soon enough. Today, accredited mining engineering programs in the U.S. produce fewer than 200 bachelor’s-level graduates per year, for an employment demand of well over 500 positions annually. This past academic year, only 600 students total were enrolled in accredited undergraduate and graduate mining engineering and related programs, while industry faces major waves of retirement. Compare that with China, which had enrollments orders of magnitude higher.

Perhaps the most significant factor in the U.S. mining workforce shortage is the perception of an industry confronting a record of environmental degradation and disproportionate economic and social impact on marginalized communities. According to a global McKinsey survey, 70% of 15- to 30-year-old respondents said that they “definitely wouldn’t” or “probably wouldn’t” work in the mining industry.

The opportunity before us is to engage and inspire the next generation of leaders for the mining and critical materials sectors with a purpose and passion for the future of the planet, for people and communities, and our energy future.

For many connected to the mining industry, including a declining number of mining schools, the Mine of the Future vision considers the technological opportunities for precision, low-impact mining, efficiently optimizing the value of products mined from earth as well as the stewardship of water and materials used in production. It involves the design of new products durable enough to be reused and recycled, closing the cycle of the circular economy for all materials sourced from mining. And it requires working transparently and in partnership with communities and business to engender a new foundation of mutual trust, respect, and acceptance, with information and reporting that is credible and independently validated.

Just as the future of mining must change, so, too, must its workforce. This vision will require talented people with diverse backgrounds, committed to making a difference, and trained in fields including geosciences, advanced manufacturing, data science, robotics, artificial intelligence, sustainability, and societal engagement.

The world’s most challenging issues require the best and the brightest minds. If we hope to achieve a clean energy future, we need an inspired engineering workforce prepared to build that future from beneath the ground up.

Dr. Walter G. Copan is vice president for research and technology transfer at Colorado School of Mines.